UK: Alstom is hopeful of confirming an order before the end of this year for its Breeze hydrogen multiple-unit trains being developed in partnership with leasing company Eversholt Rail, suggesting that the first trains could enter service ‘as early as 2022’.

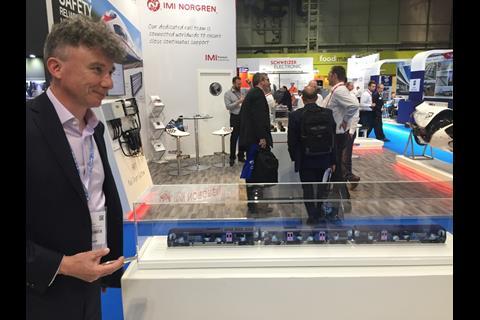

Unveiling a scale model of the three-car HMU at the Railtex trade fair on May 14, Head of Business Development & Marketing for Alstom UK & Ireland Mike Muldoon said ‘the momentum continues to build around hydrogen trains in the UK. We believe they have a key role to play in helping the railway meet government targets to remove diesel trains by 2040.’

Whilst accepting that electrification is preferable for high speed main lines and busy suburban routes, Muldoon suggested that the re-engineered fuel cell trainsets could play a valuable role on regional routes during a 15 to 20-year transition period. ‘Brand new designs for hydrogen trains will come when the market is there’, he predicted.

Alstom and Eversholt are looking to convert some of the BR-built Class 321 EMUs that date from the early 1990s. These four-car sets are ‘some of the UK’s most reliable rolling stock’, but are due to be displaced by new vehicles over the next 18 months. Conversion would be undertaken at the Alstom facility in Widnes, ‘creating high quality engineering jobs in this new, emerging sector’.

According to Alstom, the two pre-series iLint multiple-units in Niedersachsen have now passed 100 000 km of operation in passenger service since being launched in September 2018, and production of the first series fleet is in progress with more orders to follow. The Breeze would harness much of the same technology, but modified to fit the more constricted UK loading gauge.

The converted HMUs would have three roof-mounted banks of fuel cells on each of the two driving vehicles, producing around 50% more power than the iLint. Two passenger seating bays and one door vestibule behind each cab would be replaced by storage tanks. The fuel cells would feed underfloor battery packs which would also store regenerated braking energy. The current DC traction package on the centre car would be replaced by new AC drives and a sophisticated energy management system. Despite the loss of some seating space, each set of three 20 m vehicles would provide slightly more capacity than a two-car DMU with 23 m cars which it would typically replace.

Noting that other companies were also developing prototype hydrogen trains for the UK market, Alstom said it had submitted business cases for 'sensible' fleet deployment opportunities, of typically 10 trainsets or more. It noted that suitable refuelling infrastructure would have to be developed in parallel with train conversion, although this could potentially be shared with other applications. Ideally, the trains would use ‘green’ hydrogen manufactured by electrolysis using surplus renewable energy rather than ‘brown’ hydrogen from steam methane reforming.

Alstom is looking to achieve a ‘worst case’ range of around 1 000 km between refuelling, with the Breeze trains running at up to 145 km/h. Nevertheless, the first deployments would be based on ‘out and back’ diagramming with the trains returning to depot on a daily basis. This would become less of a constraint once additional fuelling infrastructure became available.