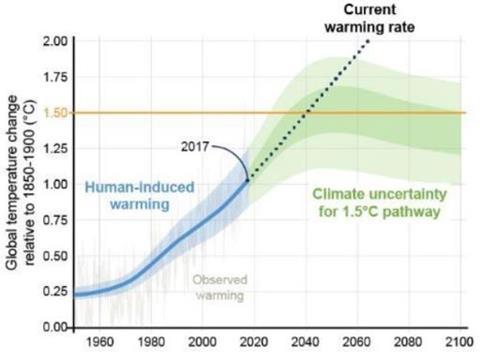

‘Rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society’ are needed if global warming is to be limited to 1·5°C above pre-industrial levels, according to an assessment by the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Presented in Incheon on October 8, the Special Report on Global Warming had been commissioned during the COP 21 summit in Paris at the end of 2016, and is due to be debated at the Katowice climate change summit next month. Pulling together research by 91 specialists from 40 countries, IPCC argues that limiting limiting global warming to 1·5°C compared to the earlier target of 2°C would offer ‘clear benefits to people and natural ecosystems’, and could go ‘hand in hand with ensuring a more sustainable and equitable society’.

Achieving the lower target would require carbon dioxide emissions to fall by about 45% from 2010 levels by 2030, reaching ‘net zero’ around 2050. Any ‘overshoot’ would have to be balanced by as-yet unproven ways of removing CO2; from the atmosphere. The report emphasises that cuts on that scale would require ‘rapid and far-reaching’ transitions in land use, energy, industrial and transport policies, among others.

So where does rail fit into this vision? The European Union is currently trying to agree a long-term strategy for reducing greenhouse gas emissions in accordance with its commitment to the Paris Agreement. With Austria currently holding the rotating presidency of the EU Council, the Community of European Railways and ÖBB hosted a round table in Wien on October 10 to look at the contribution which rail could make towards decarbonisation of the transport sector.

According to EU figures, transport is the only sector in Europe which has failed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions over the past two decades. And the global situation is no better, as economic development drives demand for mobility. Many emerging countries have seen explosive growth in road vehicle use while struggling to revitalise their rail networks.

While rail has long been seen as the ‘greenest’ mode of land transport, there is still much that can be done to improve its environmental footprint. Around 80% of all tonne-km and passenger-km on Europe’s railways are electrically hauled, and ÖBB CEO Andreas Matthä told the Wien round table that Austria’s national railway is now sourcing all of its traction electricity from 100% renewable sources.

In terms of route length, the majority of the world’s railways are not electrified. We looked in the October issue at the prospects for reducing reliance on diesel , and in our November issue we report on battery traction developments ranging from EMUs in Europe and Japan to a heavy freight locomotive in California. Many of these initiatives are supported by public funding, through research or air quality improvement grants. Studies suggest that greener traction should be cost-effective once adopted in quantity, so the key here will be to move from prototype to industrialisation.

While innovation has a vital role to play, many commentators argue that the quickest way to achieve large-scale decarbonisation is to promote modal shift from road or air to rail. CER estimates that rail freight is six times more energy-efficient than road, while emitting a ninth of the CO2; emissions. It says policymakers need to ‘come up with an effective action plan that can deliver the emission reductions needed in the transport sector, starting with a binding greenhouse gas emission target as well as modal share goals’.

Pointing out that ‘the EU has an ambitious decarbonisation agenda, set out in its 2016 strategy on low-emission mobility’, DG Move’s Director of Land Transport Elisabeth Werner agreed that ‘for sustainable transport, we need to grow the share of rail. That requires a competitive rail sector, through the full implementation of the Fourth Railway Package.’

One big challenge to modal shift is the lack of a level playing field in terms of external costs, as the rail sector has been arguing for decades. Making rail greener, more efficient and competitive achieves little while governments remain unwilling to make road or air users pay the true cost of their environmental and social impacts.

Many countries have based their economic competitiveness on the availability of ‘cheap’ transport, locating industrial plants and centres of employment to exploit the ‘flexibility’ of road. Adopting a balanced transport strategy would have a fundamental impact on businesses and lifestyles, and very few governments would willingly adopt policies that make their countries poorer or less competitive in a global market.

A genuinely sustainable approach would aim to reduce the demand for transport by all modes, while encouraging modal shift at the same time. Even then, any significant increase in rail’s share would still require a massive uplift in capacity. That raises all sorts of questions about infrastructure financing and ‘Nimby’ attitudes that hinder major developments.

Reversing the long-term trend will be far from straightforward. After all the fine words, firm action is needed to implement rapidly the ‘far-reaching and unprecedented changes’ for which the IPCC is calling. The clock is ticking.