SWEDEN: Infrastructure manager Trafikverket has put forward proposals to take in-house the management of maintenance on three sections of the national rail network, in order to provide a benchmark for its other contracts and to improve its knowledge base as an informed customer.

Although predecessor Banverket had in-house maintenance and renewals teams, all work has been outsourced since the road and rail infrastructure managers were merged into Trafikverket in 2010. However, the position has been under review by successive governments since severe winter weather and related disruption about 10 years ago revealed shortcomings in the contract arrangements then existing.

In December 2021, Minister for Infrastructure Tomas Eneroth instructed Trafikverket to assess the measures it would need to take in order to undertake ‘certain railway maintenance tasks’ under its own auspices, commenting that ‘the market for basic maintenance has not developed in a direction that is sustainable in the long term’ since it was opened up to full competition.

However, the infrastructure manager was required to pay special attention to ensuring that any proposed changes ‘do not entail negative consequences’ for continuing to procure the majority of its maintenance tasks through competition.

In its report submitted to the minister on April 20, Trafikverket accepted that it needed to develop its role as a customer ‘through increased learning’ and by taking measures to develop the market. These could involve experiments with different business arrangements or forms of contracting. It pointed out that the situation was being kept under review in collaboration with the supply industry and academia, and reiterated that whatever measures might be adopted by the government needed ‘to provide the market with stable and long-term conditions’.

Three pilot areas

In order to develop its customer competence, Eneroth asked Trafikverket to look at taking responsibility for maintenance in three geographical areas. The report suggests that using in-house staff for planning and production management would give the infrastructure manager ‘full insight into how the operational work is carried out’, but increasing the proportion of in-house resources would not bring further benefits.

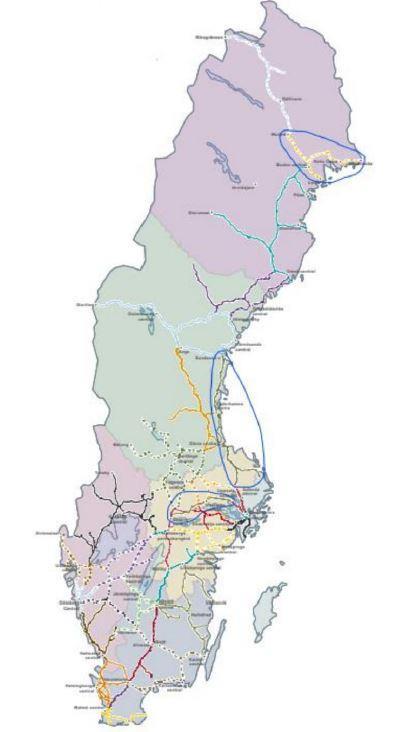

Trafikverket has identified three areas with differing traffic flows where the current maintenance contracts expire between 2024 and 2027. This would allow a new structure to be introduced at that time.

The first area to transfer to new arrangements from 2025 would cover the southern part of the Malmbanan heavy-haul iron ore railway and the adjacent Haparandabanan in the north of the country. This would provide experience with heavy freight traffic and the roll-out of ERTMS under severe winter conditions.

The following year would see Trafikverket taking charge of the Ostkustbanan between Uppsala, Gävle and Sundsvall, a double-track route with a mix of long-distance and regional passenger traffic and freight, as well as large climatic variations.

The third area to start in 2027 would be the Mälarbanan routes west of Stockholm, which carry intensive regional passenger services to and from the capital.

Trafikverket also proposes to develop new business arrangements for periodic inspection of the national network, with changed ‘responsibility interfaces’ that would allow it to develop its own competence in this area.

Its assessment is that taking the planning and production management of the three pilot areas in-house in 2025-27 would cost between SKr100m and SKr200m.

Alternative scenario

An alternative scenario would see Trafikverket taking over the full maintenance remit, including the majority of front-line staff and procuring its own resources including plant and machinery, IT systems and materials.

This would require ‘significant efforts’, and the recruitment of up to 500 more employees, and could take up to five years to prepare, the report suggests. It would entail non-recurring costs of up to SKr525m, as well as annual costs of SKr50m to SKr100m.

Trafikverket warns that there are ‘major uncertainties’ associated with a transfer of operational staff as well as the planning and management functions. It notes that ‘there is already a shortage of skills and resources in the construction industry in general and in the railway industry in particular. Uncertainties increase if the proportion of in-house operations increases in scope, and this also applies to additional costs.’ The infrastructure manager notes that its existing contractors are already competing with each other for sufficient skilled labour to deliver their contracts.

Machinery review

Regardless of the choice of a preferred structure for its in-house operations, Trafikverket proposes to review its requirements for plant and machinery from a ‘unified national perspective’, and consider whether it should procure its own common-user pool fleet rather than leaving each contractor to make its own provision.

This review would look at technical development, climate requirements, improved winter preparedness and measures to reduce barriers to entry for railway maintenance suppliers. It will also consider the scope for providing increased capacity in terms of crisis and emergency management.

The infrastructure manager believes that to ensure the best value and efficiency, it should deepen its co-operation with the machinery market, which would ensure that the railway’s needs are adequately met.